AN ATTEMPT TO READ BETWEEN THE LINES: HOW TO DECIPHER THE IDEAS OF NBU'S COUNCIL

This is a more detailed version of the article that was published 6 December 2016 online at “Novoye Vriemia”. The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and not the position of ICU Group or its shareholders.

Chairman of the Council of the National Bank of Ukraine Bohdan Danylyshyn’s policy of economic pragmatism is the quintessence of the Ukrainian school of economic thought that could be called “pragmatism-dirigisme” (with state-directed bank lending). This year, various analytical centers, which, formally, are independent of each other, have extensively promulgated this vision of economic development and national economic policy. The Ukraine school adopted this line of thinking from the Russian school of “pragmatism-dirigisme,” the brainchild of Sergey Glaziev. The underpinnings of this principle are wrong from several key macroeconomic and monetary perspectives. Nor is it new in terms of progressive economic thinking; rather, it is preserving the old.

The opening remarks of the newly-elected Chairman of the Council of the NBU, Bohdan Danylyshyn, and his numerous speeches and interviews were milestone events in early November 2016. He called for carrying out a “policy of economic pragmatism” where “the starting point of the economic growth policy” must be “the increase of fixed investment” through “neo-Keynesian methods, such as carrying out productive monetary emission” (base-money creation by the state and then state-directed directed lending by commercial banks to non-bank businesses, both state and privately owned).

The position of the Chairman of the Council of the NBU is essentially in agreement with the ideas propounded in the document “The Policy of Economic Pragmatism” (file no longer on website) of the Kyiv-based Institute of Socio-Economic Studies (ISES), which is headed by the former Minister of Economic Development, Anatoliy Maksiuta.

Similar points were made in the report “The Policy of Monetary Expansion in the Growth and Development Support” by the Razumkov Centre, a Kyiv-based think tank (file no longer on website). It also calls for “the investment” through “the productive emission” and “the filling of the economy with ‘ready cash’”.

In early 2016, the group of experts who created The Strategy of Banking System Development for 2016-2020, are ideologically very close to the authors of the reports mentioned above. The discussion in Strategy and its subsequent promotion were made by the Verkhovna Rada Committee on Financial Policy and Banking Activity.

Analysising these documents, opinions and discourse of Mr. Danylyshyn, Mr. Maksiuta and others of the Razumkov Centre and VR Committee show that they adhere to the economic school of “pragmatism-dirigisme.” This philosophy has been developing for a long time and has put down roots in Ukraine. In an interview, Valeriy Geyets, a leader in the Ukraine's economics academic circles, revealed that his worldview has been greatly influenced by “Grzegorz Kołodko's economic school of thought that advocates economic pragmatism.” The abovementioned documents contain mostly references to Russian-language academic research and Russian sources in particular. ISES is talking about “dirigisme” in terms of a financial “boost”. This particular term, as well as the essence of this process, is taken from the book “Financial Strategies of Economy’s Modernization: the World’s Practice” published by the Russian Academy of Science under the editorship of Yakov Mirkin, Professor and Doctor of Science in Economics.

However, if you immerse yourself in the information space of the Russian Federation, there is a lively and frank discussion going on about economic policy-making. You’ll see that the doctrine of “pragmatism-dirigisme” is well rooted there. Its main proponent, Sergey Glaziev, a long-time economics advisor to President Putin, was also, until recently, an honorary member of Ukraine's National Academy of Science.

Ironically, nowadays, “pragmatism-dirigisme” is actively promulgated on the Moscow-based TV channel “Tsargrad” where you’ll hear the same things mentioned above like “productive emission”, “strategic planning”, “old/new economic order”, “growing by means of fixed investment,” in addition to criticising liberalism. “Pragmatism” and “dirigisme” are cherries on the cake in this information space. The most audacious explanation made another day by Glaziev about the need for Russia’s economy to transition to the new model based on this doctrine goes like this: “We are on the border of a World War . . . the US will fight the battle for the world domination to the last Ukrainian.”

At the end of the day, and solely from the macroeconomic point of view, the economic school of "pragmatism-dirigisme" neither at its Ukrainian centre nor from its Russian birthplace, is based on the neo-Keynesian school, which the head of the Council of NBU is espousing.

What, then, are the nuances of this discourse about “pragmatism” and a “financial boost” through the “productive emission” on the one hand and “neo-Keynesian theory” on the other?

The Chairman of the Chamber of the Council of NBU and his like-minded fellows look to the experience of the Western and Asian economies where, since the crisis of 2008, central banks have been conducting QE, or as they would call it, “the emission of money for the recovery of economy.” They point out that QE didn’t cause inflation, but they are overlooking a few facts.

Until recently, QE was conducted with the approval of economic policymakers and against a background of fiscal consolidation, that is, a reduction of the deficit and public debt levels. Due to such fiscal policy, inflation not only remained low, but was lower than the declared levels, or targets that the central banks were trying to achieve. However, this year, the developed Western economies (including Japan) admitted that use of these extraordinary measures of monetary policy did not relaunch economic growth. Brexit and Trump’s win were no accident; they were the direct result of this failed policy. Due to them, it is only now that we are seeing the beginning of shifts in economic policy towards more efficient use of budget expenditures. Political consensus in the West is to increase government expenditures for infrastructure repair and construction. The previous policy of fiscal consolidation is off the table, at least for the short and medium term. We are also starting to see a shift in the Western world away from economic liberalism toward more active government intervention.

The Ukraine ideologists of the “pragmatism-dirigisme” doctrine are only looking at the monetary part of this story and with a rather simplified understanding of what “money emission” is at that. They’re omitting the fiscal part of the equation, just as their Western counterparts did. At the same time, they are juggling terms such as the need for an “economic boost” by attempting to tie it to neo-Keynesian theory.

So, where are the false underpinnings of “pragmatism-dirigisme” in my opinion?

First, I don’t see an appropriate recognition in this doctrine for the current level of leveraging in the foreign currency debt by government and non-government sectors and policy that should be implemented to address this issue. Instead, “The Policy of Economic Pragmatism” from ISES, which is really an expression of the worldview of Bohdan Danylyshyn, calls for the creation of quasi-sovereign economic operators whose liabilities should be covered by the government’s guarantee for both external and internal creditors. Given established practices in Ukraine's financial markets, these recommendations should allow the newly-established quasi-sovereign development entities to borrow, except from external markets, domestically in Hryvnia and in foreign currencies. Instead, the doctrine tolerates further foreign-currency leveraging by government and quasi-government entities, which is a macroeconomic issue in and of itself, and it paves the way for the next financial crisis.

Second, directly and indirectly, both the authors of these documents and ideologists in the media are advocating for the continuing restraint of any kind of floating FX regime. Return to a fixed FX rate is not only likely, but also the most probable outcome if this doctrine is implemented.

Third, neo-Keynesian theory, as well as monetarism and other mainstream economic schools of thought, overlooked the global financial crisis in 2007-08. There is a well-known saying of the former Governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, that economic principles that formed the economic policy-making of the G20 countries prior to the 2008 crisis mostly ignored the intellectual legacy of the great economist Keynes. And this is why the comparison made by the “pragmatism-dirigisme” doctrine to neo-Keynesian theory is wrong.

Fourth, to a large extent, this doctrine is following the so-called Loanable Funds Theory, which, in turn, has a wider circle of followers among neo-Keynesians and many decision makers in the governments and businesses worldwide. Briefly, this is a monetary-policy idea that says to have a credit, then either savings, or money, or the emission of “ready cash” (banks' reserves) are needed, meaning that the presence of money creates credit. Actually, within the scope of this paradigm, the ideologists of “pragmatism-dirigisme” speak about the need for “productive monetary emission”—or directed lending to non-bank businesses—for the purpose of developing industry and supporting other parts of the economy. And here is where the key mistake arises. This approach relies on the assumption that the money multiplier (a ratio between money supply and money base) not only exists, but is more or less stable (in Ukraine it equals to 3x). Meaning, when base money grows, there will be predictable growth in the money supply. But, based on the observation of monetary stimulation in developed countries since 2008, the money multiplier effect didn’t work. Despite central banks growing the monetary base via QE, bank lending and corresponding growth in the money supply remained sluggish.

Ideologists of “pragmatism-dirigisme” may argue that if they influence the process in NBU through “productive monetary emission,” it will work in the desired fashion. I don’t think it will. I’ll use as an example the latest experience of the advanced countries that they point to. After many years of very slow economic recovery and the extraordinary policy steps of the central banks to increase the money base, it has taken the recent protest voting of democratic elections in the US and UK for the thinking of economic-policymakers to change toward what they should have done from the beginning of the crisis. Namely, it is about optimizing the stimulation efforts between the monetary side and—as important—from the fiscal policy side.

Fifth, according to the traditional thinking in economic development, the focus of “pragmatism-dirigisme” is on fixed-asset investments with the purpose of supporting the export-oriented model, and the exports of goods produced by a modernized industrial sector of Ukraine in particular. The export model works only when there is a strong external demand. By analogy, this makes a second emergence of China on the world’s economic map unlikely. It is important to point out that this focus on investment indicates that this approach is not new. Rather, it is well within mainstream economic thought, which says that investment growth (as a share in GDP) generates both the growth of goods and services supply, and automatically grows aggregate demand. But, in fact, the opposite is true—the growth of demand will not catch up with the growth of supply.

Sixth, the discourse around of the “pragmatism-dirigisme” doctrine and its main proponents in Ukrainian media are marked by the discontent over the NBU's current policy approach of stress-testing the banks and requiring them to re-capitalize. This indicates that deregulation of the banking sector (no stress-testing or much milder one and much more tolerant approach to banks' capitalization) would be a policy tool if the “pragmatism-dirigisme” doctrine were implemented. If a higher level of regulation is placed on the banks with more control over their operations (where insider lending once flourished), then the alternative, which this doctrine implies—to release controls and facilitate money-supply growth—would result in a flourishing of insider lending.

Together, these factors indicate that this doctrine rests on a false foundation. And, in fact, they are a bouquet of contradictions.

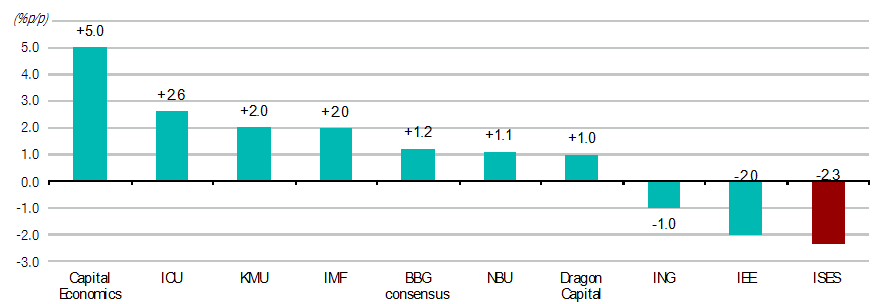

In conclusion, it is worth noting that at the beginning of the year, there was a friendly competition among those who watch Ukraine's economy for predictions of full-year real GDP growth for 2016. ISES, which produced “Policy of Economic Pragmatism” in first place and is part of the network that lobbies “pragmatism-dirigisme” doctrine into Ukraine's authorities mindset, took part (see chart below).

ISES put forward the most pessimistic forecast. They expected the economy to shrink at the rate of 2.3% YoY. This forecast was essentially different from others including ICU’s (disclosure: we projected a 2.6% YoY increase). De facto, this year there will be an increase of 1.5–1.6%. Considering all the above mentioned from the criticism of “pragmatism-dirigisme” doctrine, a follow-up question comes to mind whether this forecast (down by 2.3%) is symbolic one.

Chart: Real GDP projections for 2016 as of 1 March 2016 (% YoY)

Source: ICU. Note: KMU – Cabinet of ministers of Ukraine; NBU – National Bank of Ukraine; IEE and ISES are Kyiv-based policy think-tanks.