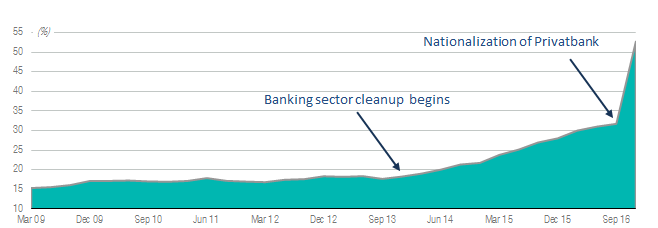

A Super State Bank: PrivatBank Has Been Nationalised. What Comes Next?

PrivatBank has become state-owned. On the one hand, the bank system became more stable and the large part of payment infrastructure no longer depends on shareholders of only one private bank. On the other hand, solving the problem of a “too big to fail” bank has created the problem of a “too big to sell” bank. If the plan to merge PrivatBank and Oschadbank is implemented, it will be impossible to sell the newly created giant bank to a private investor without risking to transfer the control over the blood vessels of Ukrainian economy into private hands. Moreover, the bank merger itself is quite a complicated and long-term procedure. The bank merger of two smaller banks, Ukrsotsbank and UniCredit, which took almost three years, is a good example.

Too big to sell

The concentration of infrastructure. The utmost importance of the bank for the payment infrastructure was among the key factors why PrivatBank was nationalised and not liquidated. Around a half of all bank cards of POS terminals and ATMs belong to PrivatBank. Its nationalisation resulted in 74% of all cards in circulation being issued by state-owned banks. As for the POS terminals and the number of bank braches, the share of state-owned banks amounts to 77% and 60% respectively.

It is not clear whether these numbers are going to decrease. If the state does not fail to manage all this infrastructure more or less properly – while the attempts of a technological breakthrough by Oschadbank give a reason for optimism – customers will be encouraged to switch to the services of one of the four state-owned banks. It is also obvious that administrative barriers to further growth, which were put in the past, are no longer a threat to PrivatBank. Since it became 100% state-owned, it can easily provide services to the recipients of social welfare payments and pensions, and apparently, regain its status of the agent of the Deposit Guarantee Fund, which was de facto lost.

However, at the same time, selling this giant poses a new problem. For obvious reasons, “The Principles of State Banking Sector Strategic Reforming”, adopted almost a year ago, do not include specific plans for selling PrivatBank. Still, the document presumes “a growth of the government’s share through possible changes in the banking sector of the country.” The spirit of the document suggests an intention to significantly reduce the state’s share through a partial or complete sale of the bank number one. It is doubtful that private banks will be able to catch up with PrivatBank in terms of the number of cards or terminals in the next 2-4 years. Thus, selling PrivatBank in its current form would pose a risk of monopolisation of the market by its new owners.

This is relevant to both the infrastructure and resource base since 36% of all private deposits were placed in PrivatBank. Although the media alarmed that people were withdrawing 2 bln UAH cash from ATMs daily immediately after the temporary administration was imposed (as it turned out, the usual daily figure was 1.3 bln UAH), the panic is now subsiding. Therefore, most of deposits will stay at the bank, which will pose additional risks for its possible future privatisation.

In such a case, the prospect of merging Oschadbank with PrivatBank, which has been discussed since the first days of the nationalisation, makes the potential denationalisation of both institutions less probable. Transferring the control over such a super bank is a question of national security and is thus bound to be postponed. In the meantime, the state will keep control over the bank and it is hard to imagine that a hypothetic FUIB, Aval or UkrSibbank can catch up with this super bank in terms of the market share.

The Lord of the Rates

The Ministry of Finance is now able to have a bigger influence on the rates. One of the two reasons why PrivatBank succeeded to amass so many private funds was its usability, adaptability, and a large chain of branches and cash-in ATMs. Another equally important reason was the high rates the bank offered. They often were a few percentage points above the market average. After the high-risk banks with the highest rates such as Delta, Finance and Credit, VAB Bank and others were removed from the market, there have not been so many options with high rates left. In general, PrivatBank had created a paradoxical situation in which the leader of the banking sector pays a premium on the average price of bank deposits. In neighbouring countries (Poland, Hungary, and the Russian Federation), local leaders hold from 20% to 43% of the deposit market share, however, their rates are noticeably lower than the average rates. Local depositors are ready to forgo higher interest over the safety of a country’s largest and most reliable financial institution.

Since the Ministry of Finance controls more than half of the banking system, it can try to help the NBU to gradually cut interest rates. Of course, each state-owned bank is directly governed by an independent board. However, as a shareholder, the state will encourage such a cut because it will help refinance part of the public debt at a lower price.

Currently, PrivatBank and Ukreximbank have an advantage of the 100% state guarantee on private deposits, the advantage Oschadbank alone used to enjoy. Still, the latter remains outside of the Deposit Guarantee System and thus avoids paying contributions to the Deposit Guarantee Fund. The State guarantee is aimed at assuaging doubts of the most cautious depositors who prefer playing it safe. Apparently, such a measure is rather a reputational step aimed at reducing panic among depositors and maintaining the bank’s liquidity. Generally speaking, this guarantee resembles a nuclear weapon – no one takes the idea of using it seriously, however, it comforts those who possess it.

In the medium term, such a guarantee will do more harm than good, since it will distort market mechanisms by artificially stimulating the resource flow to the state-owned banks. Such a situation can be hardly seen as a fair market competition among banks. Again, “The Principles of State Banking Sector Strategic Reforming” stipulate that the 100% guarantee of deposits should be cancelled for Oschadbank rather than applied to two more banks. It would be best to sell at least a small percentage of shares of these banks since the guarantee applies to 100% state-owned banks. This brings us back to the problem of selling the bank.

Is the Government Administration Efficient?

Channeling financial resources to those sectors of economy where they can be used in the most efficient way is one of the key tasks of a banking system. For a long time, state-owned banks have occupied a particular niche focused on issuing loans to big state-owned and private companies and projects. These were followed by energy efficiency programs and lending to small and medium-sized businesses in collaboration with international finance companies. Today, after the state-owned banks increased their share in assets to more than 50% of the banking system, they should expand their business scope considerably.

Lending to the state is another issue. 35-40% of all assets of the “old” state-owned banks (Oschadbank, Ukreximbank, and Ukrgazbank) is made up by investments in the government bonds, including those that were used for additional capitalisation of these financial institutions. Together with 116 bln UAH provided to patch the hole in the PrivatBank balance, investments in government securities will make up an equivalent of $10 bln or 40% of the total balance of these four banks. Those who believe that the credit policy of the state-owned banks bears corruption risks may see as positive the fact that almost 15% of the government debt are concentrated in the hands of the state-owned banks. In the past, financing large projects by the state-owned banks was a burden on taxpayers who virtually paid for the additional capitalisation of these banks. And when the bank’s assets are de facto invested in the government debt, it leaves much less room for manoeuvre.

On the other hand, over UAH250bn of government bonds on the state owned banks’ balance sheet provides enough resources for lending. These bonds can be sold [1] on the market or easily used as a collateral for the NBU loans. The policy of further lowering the rates will make this resource cheaper for the banks since the cost of these loans depends directly on the NBU interest rate.

Thanks to nationalizing PrivatBank, the state now has the biggest credit card loans portfolio, significant portfolios of other consumer loans, and powerful transactional business. Whether these needs of Ukrainian economy are fully met depends on how efficient the newly appointed administration of the bank will be.

Sources: NBU, calculations by ICU.

Bank cards (active) as of the 3rd quarter of 2016

Sources: NBU, calculations by ICU.

POS terminals as of the 3rd quarter of 2016

Sources: NBU, calculations by ICU.

Retail deposits as of the 3rd quarter of 2016

Sources: NBU, calculations by ICU.

Notes:

[1] government bonds used for the recapitalisation of the banks are classified as “held to maturity” on the bank balance sheet. Consequently, they cannot be sold.